The roots of yoga reach down to primordial myth that nurtures the entire human race. Cultures throughout the world share the myth of “the world tree,” sometimes known as “the tree at the navel of the earth.” The Indian yoga masters, the shamans of Siberia (for whom the tree was a nursery as well as a cosmic ladder), the Persian priests, the ancient Celts, and even the Vikings knew this tree well. The Siberian shaman’s drum was said to be made from the wood of the world tree.

The Quran refers to the “Tree of Immortality” or the “Tree of Life”—very similar to the trees, “of Life,” and of “the Knowledge of Good and Evil,” in the Jewish and Christian Genesis. Even before Genesis, as long ago as 4,000 B.C., the Babylonians thought the sacred tree was somewhere near the ancient city of Eridu. In its leaves was the throne of Zikum, queen of the heavens; its trunk was the holy abode of Davkina, the Earth Goddess.

In Aztec and Mayan cultures, the world tree, Yax-cheel-cab, is filled with fruit,

from apples to figs—even breasts. Mayans worshipped the kakaw tree,

source of cacao and chocolate, discovered by the gods on a mountain. One

depiction of the chocolate tree clearly reveals its identification with

the human spine. Those “plumps” depict not only the cacao fruit but

breasts, the source of all nurture.

from apples to figs—even breasts. Mayans worshipped the kakaw tree,

source of cacao and chocolate, discovered by the gods on a mountain. One

depiction of the chocolate tree clearly reveals its identification with

the human spine. Those “plumps” depict not only the cacao fruit but

breasts, the source of all nurture.In the creation myth of the Maori, the first thing formed from the navel of the void was the world-tree, from whose buds emerged all creation. Just as in the Garden of Eden, the world tree abounds with birds and animals—and the inevitable reptile. In Norse mythology, the sharp-eyed eagle stood watch in Yggdrasil’s upper branches to ward off the serpent Niddhogg’s constant assaults.

The Plumed Serpent gave cacao to the Maya—its symbolic depiction almost identical to the Greek caduceus, the healing rod-tree carried around which snakes are coiled, carried by the god Hermes (Mercury). In kundalini yoga belief the serpent is coiled around the human spine (the word kundalini itself means “coiled”).

The Plumed Serpent gave cacao to the Maya—its symbolic depiction almost identical to the Greek caduceus, the healing rod-tree carried around which snakes are coiled, carried by the god Hermes (Mercury). In kundalini yoga belief the serpent is coiled around the human spine (the word kundalini itself means “coiled”).The ancient Egypt hieroglyphic character ankh meant "life" or

“breath of life.” A tree stylized as a straight rod with a serpent coiled around it, the ankh was considered by some as a predecessor of the Christian cross (itself another world tree). The ankh was also known as the “key of the Nile” or “crux ansata” (Latin, meaning "cross with a handle").

“breath of life.” A tree stylized as a straight rod with a serpent coiled around it, the ankh was considered by some as a predecessor of the Christian cross (itself another world tree). The ankh was also known as the “key of the Nile” or “crux ansata” (Latin, meaning "cross with a handle").In universal tree mythology, diametrically opposite forces hold life and death in balance; while the tree itself remains eternally stationary.

In the pre-classical Homeric Odyssey the tree of life is the living marriage bed of Penelope. She uses her knowledge of how Odysseus carved it from the living tree around which he built their palace to identify her husband when he returns home disguised as a beggar after twenty years of wandering.

The world tree is the post that connects heaven, earth, and the underworld; its roots mirror its branches. It links the conscious with the unconscious mind.

Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus described the world tree in one of the few cryptic fragments that have come down to us through the ages: “The way up and the way down are the same thing.” Find the world tree, and the shaman has access to the spiritual realms of the heavens and the dark earthy knowledge of the underworld. In the Torah, Jacob’s ladder is guarded by angels as you climb, by demons as you descend. Not surprisingly, Carl Jung, one of the founders of modern psychology, identified the tree with the axis mundi, the unmoving axle on which the world turns. Jung saw it as a personal “meridian,” or psychological umbilical connecting each individual to the divine source in its branches and to the dark vaults of our animal nature in its roots.

In every culture, the Tree of Life is hidden and can be found only by the initiate--the Druidic priest, the ecstatic Dionysian, or the son of God who dies on the tree for the sins of all humanity then descends from it to hell, and finally climbs it to his enlightened seat at the right hand of his father. When you practice yoga, you reenact the ancient shamanic journey toward “truth” or “enlightenment,” as your meditative breath climbs up and down the world tree. Padma Purana and Skanda Purana enumerate the many benefits to be secured from reverentially approaching and worshipping the world tree.

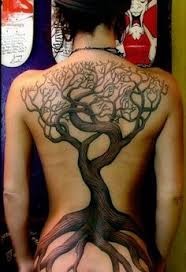

In ancient Hindu culture, as the Buddha discovered under that Bodhi tree (ficus

religiosa), the Tree of Life is the human spine, hidden from the living, visible only to the dead—and to the practitioner who explores it with his or her breath. The gods and goddesses in its high branches are all rooted in the trunk, which is identified with Brahman, the ultimate Reality. The atman, the individual soul, finds enlightenment by traveling up and down this internal tree as it approaches identity with Brahman. The kundalini serpent coils up from the spine-tree’s roots, its navel holds the power of rebirth, the celestial Third Eye sits at its crown and the initiate, the yogi, climbs with his breath up and down the tree at will.

Like any tree, the hidden spine bends with the wind-breath. The more it bends the longer it lives, the more life it experiences and the stronger it becomes. “There is an eternal tree called the Ashvattha, which has its roots above and its branches below,” says Katha Upanishad, a text which unveils secrets of life and death.

From “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “the Green Man,” to the Yule tree coiled with lights to light your way home through the dark, to Virgil’s “golden bough,” to Robert Graves’ The White Goddess, to J.R.R. Tolkien’s Ents, to the Tree of Souls in James Cameron’s Avatar, symbols of the world tree are as universal as human backbones. Cutting the tree down is the end of communication between higher and lower worlds. Strengthening it through the initiate’s ritual discipline leads to physical health and spiritual enlightenment. In Exodus, God turned Moses’ rigid staff into a snake and back into a staff which signifies the power of keeping the spine as supple as a serpent: It is better to bend than to break.

Read more Ken Atchity Huff Posts

Read more Ken Atchity Huff Posts

No comments:

Post a Comment